Definition: The inner masculine side of a woman. (See also anima, Eros, Logos and soul-image.)

Like the anima in a man, the animus is both a personal complex and an archetypal image.

Woman is compensated by a masculine element and therefore her unconscious has, so to speak, a masculine imprint. This results in a considerable psychological difference between men and women, and accordingly I have called the projection-making factor in women the animus, which means mind or spirit. [It] corresponds to the paternal Logos just as the anima corresponds to the maternal Eros. [“The Syzygy: Anima and Animus,” CW 9ii, pars. 28f.]

The animus is the deposit, as it were, of all woman’s ancestral experiences of man – and not only that, he is also a creative and procreative being, not in the sense of masculine creativity, but in the sense that he brings forth something we might call … the spermatic word. [“Anima and Animus,” CW 7, par. 336.]

An Unconscious Mind

Whereas the anima in a man functions as his soul, a woman’s animus is more like an unconscious mind. [At times Jung also referred to the animus as a woman’s soul. See soul and soul-image.] It manifests negatively in fixed ideas, collective opinions and unconscious, a priori assumptions that lay claim to absolute truth. In a woman who is identified with the animus (called animus-possession), Eros generally takes second place to Logos.

A woman possessed by the animus is always in danger of losing her femininity. [“Anima and Animus,” CW 7, par. 337.]

No matter how friendly and obliging a woman’s Eros may be, no logic on earth can shake her if she is ridden by the animus. … [A man] is unaware that this highly dramatic situation would instantly come to a banal and unexciting end if he were to quit the field and let a second woman carry on the battle (his wife, for instance, if she herself is not the fiery war horse). This sound idea seldom or never occurs to him, because no man can converse with an animus for five minutes without becoming the victim of his own anima. [“The Syzygy: Anima and Animus,” CW 9ii, par. 29.]

A Helpful Psychological Factor

The animus becomes a helpful psychological factor when a woman can tell the difference between the ideas generated by this autonomous complex and what she herself really thinks.

Like the anima, the animus too has a positive aspect. Through the figure of the father he expresses not only conventional opinion but – equally – what we call “spirit,” philosophical or religious ideas in particular, or rather the attitude resulting from them. Thus the animus is a psychopomp, a mediator between the conscious and the unconscious and a personification of the latter. [Ibid., par. 33.]

Jung described four stages of animus development in a woman. He first appears in dreams and fantasy as the embodiment of physical power, an athlete, muscle man or thug.

In the second stage, the animus provides her with initiative and the capacity for planned action. He is behind a woman’s desire for independence and a career of her own.

In the next stage, the animus is the “word,” often personified in dreams as a professor or clergyman.

In the fourth stage, the animus is the incarnation of spiritual meaning. On this highest level, like the anima as Sophia, the animus mediates between a woman’s conscious mind and the unconscious. In mythology this aspect of the animus appears as Hermes, messenger of the gods; in dreams he is a helpful guide.

Projection

Any of these aspects of the animus can be projected onto a man. As with the projected anima, this can lead to unrealistic expectations and acrimony in relationships.

Like the anima, the animus is a jealous lover. He is adept at putting, in place of the real man, an opinion about him, the exceedingly disputable grounds for which are never submitted to criticism. Animus opinions are invariably collective, and they override individuals and individual judgments in exactly the same way as the anima thrusts her emotional anticipations and projections between man and wife. [“Anima and Animus,” CW 7, par. 334.]

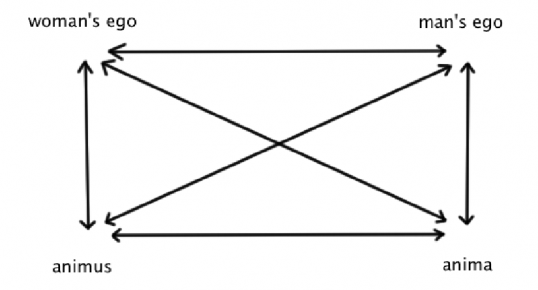

The existence of the contrasexual complexes means that in any relationship between a man and a woman there are at least four personalities involved. The possible lines of communication are shown by the arrows in the diagram. [Adapted from “The Psychology of the Transference,” CW 16, par. 422.]

The Task

While a man’s task in assimilating the effects of the anima involves discovering his true feelings, a woman’s task is becoming familiar with the nature of the animus by constantly questioning her ideas and opinions.

The technique of coming to terms with the animus is the same in principle as in the case of the anima; only here the woman must learn to criticize and hold her opinions at a distance; not in order to repress them, but, by investigating their origins, to penetrate more deeply into the background, where she will then discover the primordial images, just as the man does in his dealings with the anima. [“Anima and Animus,” CW 7, par. 336.]

© from Daryl Sharp’s Jung Lexicon, Inner City Books, reproduced with kind permission of the author.