The persona is that which in reality one is not, but which oneself as well as others think one is. – Carl Jung, CW 9i, par. 221

We have a name, perhaps a title, perform a function in the outside world. We are this, that or the other. To some extent all this is real, yet in relation to our essential individuality, what we seem to be is only a secondary, superficial reality.

Jung describes the persona as an aspect of the collective psyche, which means there is nothing individual about it. It may feel individual—quite special and unique, in fact—but our persona is on the one hand simply a social identity, and on the other an ideal image of ourselves.

Like any other complex, one’s persona has certain attributes and behaviour patterns associated with it, as well as collective expectations to live up to: a struggling writer, for instance, is a serious thinker, on the brink of recognition; a teacher is a figure of authority, dedicated to imparting knowledge; a doctor is wise, versed in the arcane mysteries of the body; a priest is close to God, morally impeccable; a mother loves her children and would sacrifice her life for them; an accountant knows his figures but is unemotional, and so on.

That is why we experience a sense of shock when we read of a teacher accused of molesting a student, a doctor charged with drug abuse, a priest on the hook for pedophilia, a mother who breaks her children’s bones, or kills them; an accountant who fiddles the books; a pillar of the community caught with his pants down.

The development of a collectively suitable persona always involves a compromise between what we know ourselves to be and what is expected of us, such as a degree of courtesy and innocuous behaviour. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with that. In Greek, the word persona meant a mask worn by actors to indicate the role they played. On this level, it is an asset in mixing with other people. It is also useful as a protective covering. Close friends may know us for what we are; the rest of the world knows only what we choose to show them. Indeed, without an outer layer of some kind, we are simply too vulnerable. Only the foolish and naive attempt to move through life without a persona.

However, we must be able to drop our persona in situations where it is not appropriate. This is especially true in intimate relationships. There is a difference between myself as an analyst and who I am when I’m not practicing. The doctor’s professional bedside manner is little comfort to a neglected mate. The teacher’s credentials do not impress her teenage son who wants to borrow the car. The wise preacher leaves his collar and his rhetoric at home when he goes courting.

By handsomely rewarding the persona, the outside world invites us to identify with it. Money, respect and power come to those who can perform single-mindedly and well in a social role. No wonder we can forget that our essential identity is something other than the work we do, our function in the collective. From being a useful convenience, therefore, the persona easily becomes a trap. It is one thing to realise this, but quite another to do something about it.

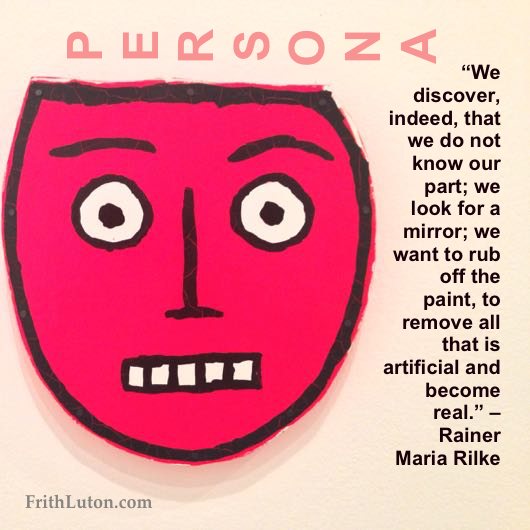

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke put it quite well:

We discover, indeed, that we do not know our part; we look for a mirror; we want to rub off the paint, to remove all that is artificial and become real. But somewhere a bit of mummery that we forget still sticks to us. A trace of exaggeration remains in our eyebrows; we do not notice that the corners of our lips are twisted. And thus we go about, a laughing-stock, a mere half-thing: neither real beings nor actors. – Rilke, The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge, p. 217

Identification with a social role is a frequent source of midlife crisis. This is so because it inhibits our adaptation to a given situation beyond what is collectively prescribed. Who am I without a mask? Is there anybody home? I am a prominent and respected member of the community. Why, then, is my wife interested in someone else?

Many married people cultivate a joint persona as “a happy couple.” Whatever may be happening between them, they greet the world with a united front. They are perfectly matched, the envy of their friends. What goes on behind the curtains is anybody’s guess, and nobody’s else’s business, for sure, but how many “happy couples” feel trapped in their persona and stay together simply because they don’t know who they are alone?

We cannot get rid of ourselves in favour of a collective identity without some consequences. We lose sight of who we are without our protective covering; our reactions are predetermined by collective expectations (we do and think and feel what our persona “should” do, think and feel); erratic moods betray our real feelings; those close to us complain of our emotional distance; and, worst of all, we cannot imagine life without it.

Assuming we recognise the problem, and suffer because of it, what are we to do about it? Personal analysis is a possibility for those who can afford it. Otherwise, some reading in the literature of depth psychology would not go amiss. But avoid “quick-fix” books, confessional memoirs by those who would seduce you into imitating them. Your task is to discover who you are.

Here are some tips:

1) Pay attention to your dreams; mull over their content, and don’t think you have to “understand” them to get the message.

2) Monitor your feelings in both intimate and social situations.

3) Become aware of how and when you use your persona for legitimate reasons, and when you are simply hiding behind it.

4) Think about what it means to lead an authentic life.

© Daryl Sharp, Digesting Jung, used with the author’s permission